The following are the notes from the talk given at the ACG public meeting in Leicester on 10th November 2018

The following are the notes from the talk given at the ACG public meeting in Leicester on 10th November 2018

In this centenary of the end of the First World War and the media

hyping of Remembrance Day we have stories like “How Lloyd George Ended

the War” along with praise for Marshal Petain, the arch-militarist and

leader of the Vichy regime from French President Macron. We are told the

Allies were fighting for “civilisation” and democracy against Prussian

militarism. Curiously the German Empire from 1871 to 1918 (and the

North German Confederation before it in 1867) had universal male

suffrage whereas universal male suffrage was not introduced in Britain

until 1918 (women in both Britain and Germany had to wait until after

the War for any voting rights). But how did the World War Really end? In

fact, it was the working class that brought about the end of the War

through disorder, riots, mutinies, strikes and indeed two revolutions.

The First World War was a watershed for the workers movement. The

majority of the Social Democratic Parties in Europe, including the

Labour Party, took the side of their particular states, whilst

syndicalist unions like the Confederation General de Travail (CGT) which

had promised a general strike if war broke out, caved in and were swept

away by war fever. A minority of social-democrats like the Bolsheviks

and the Menshevik Internationalists in Russia opposed the war. A

minority within the anarchist movement supported the Allies, with the

majority taking clear anti-war positions.

In fact, the Armistice signed by Marshal Foch with the German military leaders on November 11

th

1918 did not end the War. Fighting continued on many fronts with a

result that 10,000 were killed, wounded or reported missing on that day.

Indeed, the Allies continued to wage war with the new Russia created by

the February and October Revolutions long after the signing of the

Armistice. Britain and France eventually withdrew from Russia in April

1919 because of strikes and mutinies in their own countries.

In Britain and France in there was great support for the War. In

Germany there was a more subdued support for the War, whilst in the

Austro-Hungarian Empire the subject peoples-Slovenes, Czechs, Ruthenes,

Croats, Serbs, Italians etc- were tepid about mobilising. This less than

enthusiastic support for the war became more pronounced as the

Austro-Hungarian Empire quickly suffered several defeats. In Russia

there was discontent from the start and a defeatist attitude towards the

Tsarist autocracy’s direction of the war. This become more pronounced

from 1915 with the start of mutinies within the Russian Army.

In Britain the Labour Party supported the War, in France the

Socialists in general and the unions did the same, with the exception of

Jean Jaures whose anti-war stance led to his murder. In Germany the

Socialists rallied the German working class with the defence of

civilisation against Russian autocracy and barbarism. The German trade

unions banned all strikes, the only exception being the

anarcho-syndicalist FVDG whose anti-war position led to their banning by

the State. Those Socialist MPs- Liebknecht, Ruhle- who had anti-war and

internationalist positions, failed to vote against war credits in the

German Parliament on August 4

th and obeyed Party discipline. Only one socialist deputy abstained and he failed to make any political statement about this act.

The First World War followed the American Civil War in its

industrialised slaughter. Casualties began to mount and in Britain this

led to the introduction of conscription in January 1916, resulting in

draft dodging and conscientious objection. Within the Russian Empire war

weariness, exacerbated by food shortages, grew and in February 1917

women workers and housewives demonstrated on International Women’s Day

with the slogans of Down With The War! And Give Us Bread! They brought

out male workers in the factories and combined with soldiers’ mutinies

this brought about the February Revolution.

The February Revolution in Russia had immense sympathy among the

working class internationally, first of all because it was seen as a way

of ending the War.

In Germany living standards began to fall because of the war and the

allied blockade. Prices rose and inflation soared. Wages fell and by

1915-1916 many foods became scarce, with a veritable famine. However,

the rich were protected from this suffering, and this included the

officer class within the army and navy. This developed a class

consciousness and a polarisation between the ruling class and the mass

of the population. Starting in 1916 workers ignored the Social

Democratic Party and the trade unions and took part in direct action and

strikes to improve their situation.

The following year there were massive strikes throughout Germany. The

worsening food situation was aggravated by a fuel shortage. The Russian

Revolution further added fuel to the fire. In April 1917 there were

huge strikes in Berlin, Leipzig and elsewhere. 200-300,00 went on strike

in Berlin against a decrease in bread rations. In Leipzig the strike

became openly political with demands for peace without annexations, and

freedom for political prisoners.

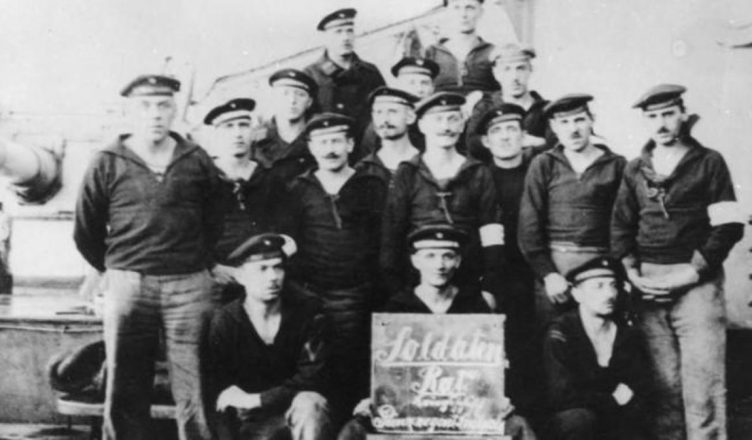

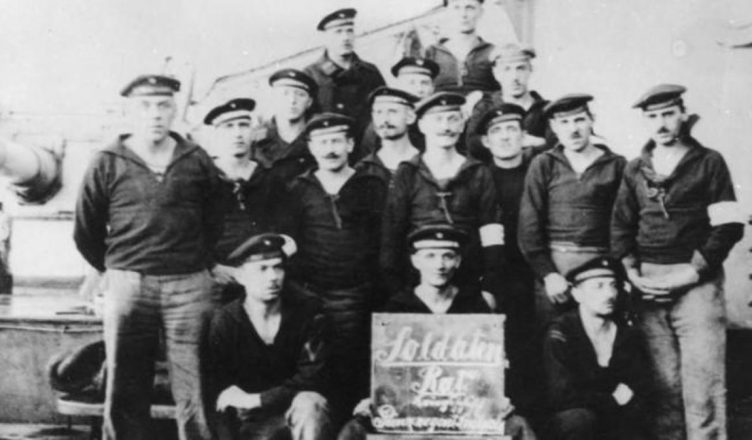

The strikes were followed by hunger strikes in the Navy against the

decrease in food rations. The officers were thoroughly hated for their

arrogance and the fact that they were better fed. In August mutinies

broke out with sympathy strikes in Wilhelmshaven harbour. The High

Command reacted with repression and two sailors were executed.

Massive demonstrations followed in German cities in November 1917. In

January 1918 in Austria, which faced a similar situation to Germany,

there were massive strikes and demonstrations because the peace talks

with Russia were failing. A massive strike followed in Berlin on January

28

th. The demands of the strike were: workers’

representation in the peace talks, better food, the end of martial law,

and a democratic regime in Germany. The strike spread to many towns and

cities., with over a million on strike in the next few days. The

authorities replied with repression, deploying police and the military.

The strike failed but in July and August wildcat strikes broke out, but

they were soon defeated. Serious defeats increased the number of

desertions. By late October the German High Command attempted a naval

attack on Britain. Sailors at Wilhelmshaven and Kiel were expecting

peace and feared that this expedition would destroy any chance of peace

negotiations and that the officer class were planning a coup d’état.

Mutinies broke out. Sailors took over Kiel forming sailors’ councils

with dock workers also creating workers’ councils. The rebellion spread

to other ports and harbours. This was followed by a spontaneous uprising

throughout Germany. Soldiers refused to fire on the demonstrators.

Workers, soldiers’ and sailors’ councils emerged everywhere. On 9

th

November the Kaiser abdicated and fled to the Netherlands. The monarchy

was ended and the new republic began peace negotiations with the

Allies. The action of the masses had brought about the end of the War.

As we have seen there was also unrest in Austria. Mutinies broke out

in Czech and Ruthene units in June 1916. And these spread in 1917 and

1918. On February 1

st, 1918 a mutiny broke at at Cattaro

(Kotor) in Montenegro with Czech and Italian sailors in the forefront. A

red flag was run up on the cruiser St George. The mutiny was crushed,

with 4 of its leading lights executed. In France where soldiers suffered

great suffering in the trenches mutinies began in May 1917. The 21

st Division revolted and its leaders were shot. Revolts followed in the 120

th Division and then the 128

th.

Twenty thousand deserted. The authorities reacted with a mixture of

repression and compromise, executing 49 whilst promising more leave and

better conditions. At least 918 French soldiers were executed during the

War. Russia had sent two brigades to fight with the French Army in

1916. Mistreatment by the French led to unrest, with an outright mutiny

taking place in May 1917. The French then moved the brigades to La

Courtine, an isolated camp in south central France. Here they held mass

meetings and refused to return to the French front, having already

suffered 4,000 casualties. They elected soldiers’ committees, refused to

recognise their officers and defied the Russian High Command. The

French military, in collusion with the new Kerensky regime in Russia,

surrounded La Courtine and began an artillery bombardment. Hundreds

died.

Within the Bulgarian Army unrest led to 600 executions. In Italy,

which had joined the carnage later than the other combatants, there was

an officer class that was drawn from the upper classes and which looked

on the rank and file with contempt. Soldiers were seen as completely

expendable resulting in huge losses. 750 executions took place with many

hundreds of other summary executions. 25,000 deserted, 5,000 defied the

callup whilst 34,000 others obeyed the call-up but deserted before

mobilisation. There were mutinies in the Army with the Ravenna Brigade

revolting in May 1917 and the Catanzaro units in July 1917. These were

brutally repressed.

Within the British Imperial Army, where there was a similar class

divide between the officers and the ordinary soldiers. Soldiers were

flogged and manacled for trivial offences. New Zealand troops mutinied

at Etaples in September 1917. Later in the month a mutiny resulted in 23

deaths at Boulogne. Strikes broke out in labour battalions on September

11

th, and mutinies continued through to 1918. Resistance to

the war expressed itself in self-inflicted injuries to avoid being sent

to the Front. As a result, 3,894 soldiers were sentenced to prison for

these actions.

It's the last Leicester ACG meeting of 2018 - we're skipping December and cramming two into November!

It's the last Leicester ACG meeting of 2018 - we're skipping December and cramming two into November!